Every December like clockwork, some genius on the internet gets on Reddit to argue that Die Hard is a Christmas movie, as if they’re the first person to ever think of that.

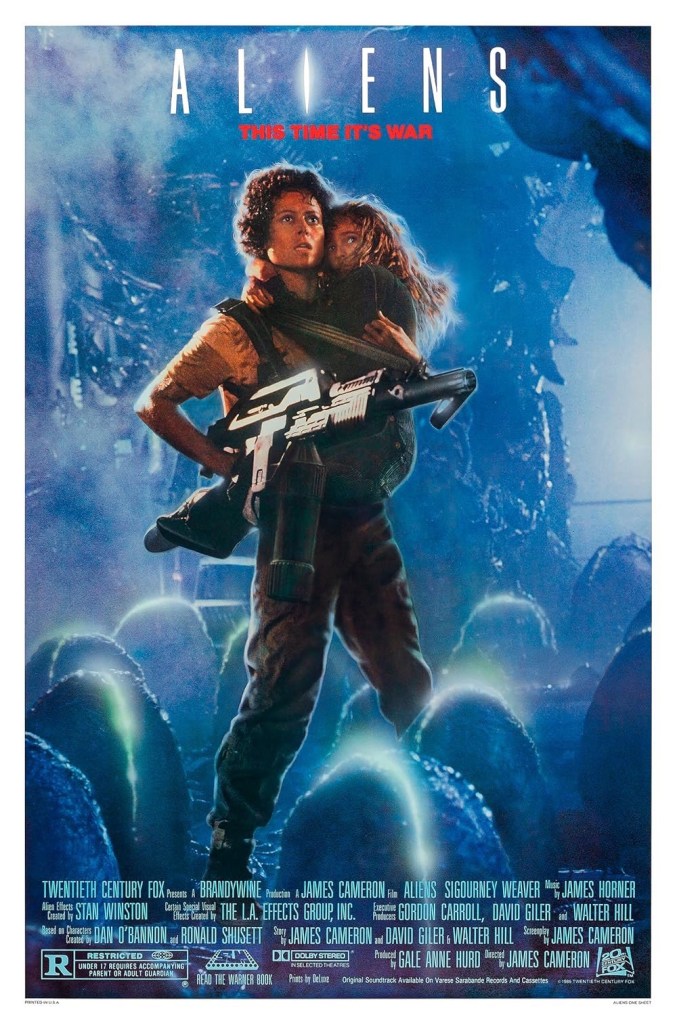

It’s such a tedious argument. Die Hard takes place at Christmas for crying out loud—the film explicitly features Christmas parties, Christmas music, and family reunification as its emotional core. Arguing that Die Hard belongs in the Christmas canon requires exactly zero imagination. And no serious person is debating it doesn’t anyway. Aliens, on the other hand, is notably overlooked. There’s no snow, no carols, no presents, no mistletoe. The film is set on a xenomorph-infested colony moon called LV-426, where the concept of seasonal holidays is meaningless and everyone is trying very hard not to get facehugged.

And yet James Cameron’s 1986 masterpiece belongs in the Christmas canon more legitimately than half the Hallmark movies clogging your streaming queue.

Ellen Ripley functions as a reluctant maternal savior in exactly the mode of every Christmas protagonist from George Bailey to Ebenezer Scrooge—she doesn’t want to go back, she’s traumatized, she’s been adrift in space for fifty-seven years, her daughter is dead, and the last thing she needs is to return to the site of her worst nightmare. But when she learns that colonists are in danger, including children, she goes anyway. Not because she’s a hero.

Because she can’t live with herself if she doesn’t.

This is the essential Christmas movie protagonist: someone who must choose between self-preservation and saving others, between cynical withdrawal and radical hope, between the comfortable lie and the terrible truth that one person’s life might matter enough to risk everything. Ripley chooses hope, and her hope has a name.

Newt.

The film’s emotional architecture rests entirely on Ripley’s relationship with this traumatized child, the sole survivor of the colony. Newt is alone, hiding in the ducts, waiting to die—she’s the lost sheep, the abandoned child, the orphan who needs rescuing. And Ripley, who has just learned her own daughter died while she was in hypersleep, finds in Newt a chance at maternal redemption. She descends into literal hell, into the xenomorph hive itself, to save one child who matters.

That’s not just thematically Christmas. That’s theologically Christmas.

The whole point of the incarnation is that God descends into the mess to save the lost, and the revolutionary claim is that each individual matters infinitely. Ripley embodies that ethic with surgical precision. When she says what may be the most Christmasy line in all of cinema, “Get away from her, you bitch!” (while wearing a power loader and facing down the Alien Queen), she’s making a maternal declaration: this child is mine, and I will tear you apart to protect her.

Which is exactly what Mary would do.

The found family dynamics reinforce this. Hudson, Hicks, Vasquez, Bishop—they’re the Island of Misfit Toys, the broken and discarded who form a makeshift family unit under impossible circumstances. Hudson is the loud complainer who reveals hidden courage, Hicks is the quiet competence who offers tenderness, Vasquez is the loyal soldier who goes down fighting, and Bishop is the synthetic person who transcends his programming through sacrificial love. They’re not related by blood. They’re bound by choice and necessity, which is the Christmas story again: chosen family matters as much as given family, and sometimes more.

Bishop deserves particular attention. He’s a created being—artificial, synthetic, designed to serve—who achieves something like transcendence through self-sacrifice. When he’s torn in half by the Alien Queen while trying to rescue Ripley and Newt, he doesn’t shut down or retreat into self-preservation protocols. He keeps reaching for them. He keeps trying to help even as his systems fail.

Now look, I’m not saying Bishop is Space Jesus… but I’m also not not saying it.

Anyway, the film gives us a synthetic person who becomes fully human through the choice to die for others, which is a fairly on-the-nose metaphor. It’s obvious Cameron intended that, because the pattern is so painfully glaring: creation achieves transcendence through sacrifice, the artificial becomes authentic through love, and the programmed entity chooses freely to give everything for someone else’s survival.

Much like Pinocchio, another Christmas classic.

The structure of the film itself follows the Christmas movie arc: descent into darkness, confrontation with death, and emergence into light through sacrifice and love. The first act establishes the world as dead—the colony is gone, hope is gone, Ripley’s daughter is gone. The second act descends into the hive, into the belly of the beast, into the place where death breeds and consumes and multiplies endlessly. The third act is resurrection: Ripley and Newt and Hicks and Bishop, barely functional and held together by sheer will, escape into the light. They’re triumphant not because they defeated the xenomorphs—the colony’s still gone, most of the marines are still dead—but because they chose love over fear, hope over despair, family over isolation.

And that’s the beating heart of every Christmas movie worth watching. Not the trappings—the snow and presents and carols and predictable romantic arcs—but the choice to believe that love matters more than death, that one person is worth saving, that family is what you make when the world falls apart. It’s a Wonderful Life works because George Bailey learns his life mattered to the people who loved him. Die Hard works because John McClane fights through impossible odds to reunite with his wife.

Aliens works because Ellen Ripley becomes a mother again by choosing to save a child who has no one else.

Also, the xenomorphs are the perfect Christmas movie antagonists precisely because they represent everything true Christmas opposes and American consumerism embodies: mindless consumption, parasitic reproduction, the reduction of persons to hosts and meat. They’re death incarnate, the ultimate negation of hope—no negotiation, no mercy, no possibility of redemption or change. And Ripley faces them armed with nothing but maternal fury and the conviction that Newt’s life is worth more than her own safety.

So yes, Aliens is absolutely a Christmas movie. It just happens to be a Christmas movie where the protagonist uses a pulse rifle and a flamethrower instead of prayers and good cheer, and the climactic confrontation involves a power loader rather than a redemptive epiphany.

But at the end of the day, aren’t those really the same thing?

The themes are there, running through every frame: hope in darkness, love as action, the choice to save one child when the world is ending.

Watch it tonight and tell me I’m wrong.

Merry Christmas.

And stay frosty.

Discover more from Beyond the Margins

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.