Not every strong female character is “woke trash”

Lisa Kuznak (@mechanicalpulp on Substack) recently posted a passionate defense of strong female characters in media, pushing back against ignorant knee-jerk dismissals.

Not every strong female character is “woke trash.” Poorly written Strong Female Characters™ are shit, but that goes for any trope.

Little girls can look up to She-Ra or Red Sonja or Ripley or Sarrah Connor just fine and it isn’t a threat to any boy’s heroes.

I’m not exactly a feminist, but holy shit the anti-woke frothing at the mouth is just as bad as the ultra-woke over seeing gorgeous women who also kick ass.

I didn’t play with barbies as a kid. I was She-Ra. I was Pink Ranger.

If you have a problem with EVERY female character with fantastical strength you might be a goon, sorry.

As Lisa points out, not every tough heroine is a threat to traditional male icons like Conan or Batman—girls can look up to She-Ra, Red Sonja, Ripley from Alien, or Sarah Connor from Terminator without diminishing anyone’s heroes. The real problem lies in poorly executed tropes that reduce women to one-dimensional figures. As a girl who grew up imagining herself as She-Ra or the Pink Ranger instead of playing with Barbies, Lisa reminds us that empowering female characters aren’t the issue—they’re vital, when crafted with care. Her words hit home in a time when cultural battles rage over representation: anti-woke backlash can be as over-the-top and reductive as the ultra-progressive extremes it criticizes.

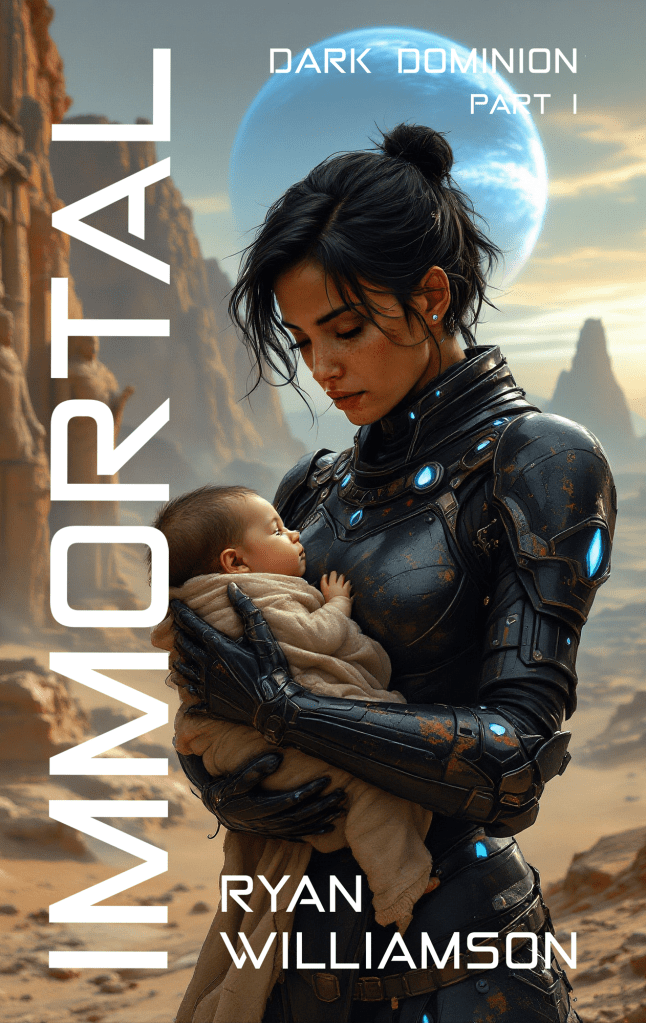

This got me thinking about Sarai izt Kviokhi, the protagonist of my forthcoming Dark Dominion sequence. In a galaxy crushed under a tyrannical god-emperor, Sarai rises as a revolutionary spark, harnessing psychic talents to lead a rebellion against deep-rooted injustice. On the surface, she might seem like a classic “Strong Female Character™” (SFC)—the kind that’s turned into a meme in today’s discussions. The SFC trope, which I’ve seen critiqued extensively in feminist media circles, often boils down to a woman who’s fierce, skilled, and unflappable, but lacks real depth, emotions, or flaws beyond a veneer of toughness. It’s the archetype that flooded 2010s blockbusters: quippy warriors in sleek armor who dominate male realms without much inner life. Writers like Sophia McDougall and Tasha Robinson have called it out as lazy—pretending to empower while equating “strength” to stereotypically masculine traits, ignoring vulnerability, connections, and true complexity.

I worked hard to ensure Sarai avoids these traps. She’s not some invincible action doll steamrolling problems with grit and one-liners; her power emerges from raw, hard-fought struggle. Starting as an amnesiac scarred by systemic abuse in a caste-divided empire where people like her are branded as cursed, Sarai rebuilds herself piece by piece. Her psychic gifts—telekinesis, cardiokinesis, telepathy, and beyond—aren’t just flashy tools for fights; they’re tied to her emotional world, surging from pain or love in ways that exact a toll. This makes her resilience feel authentic and earned, flipping the SFC’s effortless dominance on its head. Unlike heroines who shrug off horrors, Sarai confronts the ethical burden of her abilities: Does using them make her a hero or another tyrant? I poured effort into her moral gray areas, drawing from real ideas about power—how women in oppressive systems can internalize the hierarchies they’re battling.

What really sets Sarai apart, and what I strived for in her development, is her profound vulnerability—a quality the SFC trope often skips for stoic coolness. She’s a mother torn by loss, a survivor processing deep wounds, and a leader weighed down by prophetic demands. These layers pull from diverse inspirations, like Wibuiti endurance and Mešvi matriarchal traditions, making her struggles intersectional. Sarai doesn’t “girlboss” by outdoing men at their game; she forges bonds, redeems foes, and questions her role. Her relationships—with steadfast guardians, reformed traitors, and fervent followers—bring her to life, portraying strength as shared rather than solo. In Godsbane, this deepens into themes of mercy and ethical fog: Sarai offers grace to those who’ve hurt her, not from weakness, but because she sees redemption as key to breaking abuse cycles. I invested time in these nuances to make her feel real, not symbolic.

Compare this to SFC flaws in other stories. Captain Marvel in the MCU comes across as overwhelmingly capable, her “issues” brushed aside quickly, sparking complaints of flatness. Rey in Star Wars gains skills too swiftly, feeling unearned and prioritizing wow-factor over growth. Sarai sidesteps this: Her journey demands sacrifice—memory loss steals her history, tyranny robs her autonomy, pain forges her resolve. She’s akin to more layered icons like Furiosa in Mad Max: Fury Road or Aeryn Sun in Farscape: Fierce, yet shaped by scars, doubts, and ties. In crafting Sarai, I drew from SF trailblazers like Octavia Butler and Ursula K. Le Guin, who envisioned women reshaping realities through compassion and intellect, not mere brawn.

One common critique of the SFC trope—and a reason people are growing weary of it—revolves around unrealistic portrayals of women in combat. Realistically, a 90-pound woman isn’t going to overpower a 6’5”, 250-pound linebacker in hand-to-hand fighting; physics and biology don’t bend that way without some serious suspension of disbelief. Fiction thrives on escapism, of course, and there’s joy in seeing underdogs triumph through cleverness or sheer will—think Ellen Ripley outsmarting xenomorphs or Buffy Summers flipping vampires despite her slight frame. But when stories ignore these disparities without in-world logic, it can feel lazy or pandering, reducing empowerment to wish-fulfillment without stakes. I was mindful of this in Dark Dominion: Sarai is petite, drawing from Wibuiti cultural inspirations where women are often small but resilient. She doesn’t win fights through brute force alone; instead, she leverages her telekinetic talents in a specialized martial art form, turning opponents’ size against them with strategic bursts of psychic energy. This adds realism within the fantasy—her victories cost energy, focus, and sometimes moral compromise—making her feel grounded and tactical, not superhumanly invincible.

This approach allows for escapism “within reason,” as Lisa might say. Sarai’s combat style isn’t about proving she’s “as strong as the boys”; it’s about outthinking and adapting, subverting traditional power dynamics. It echoes real-world martial arts like aikido or wing chun, where redirection triumphs over raw muscle, while her psychic edge fits the genre’s speculative freedom. By rooting her strength in vulnerability—exhaustion after battles, ethical fallout from using talents lethally—I aimed to create a character who inspires without alienating. Little girls (and boys) can admire her not just for kicking ass, but for her intelligence, empathy, and growth, proving that true strength isn’t about dominating—it’s about enduring and evolving.

Moreover, Sarai isn’t idealized as perfect, which I deliberately avoided to counter SFC criticisms. She stumbles, lured by revenge and authority’s pull, mirroring women’s real complexities under pressure. This addresses why folks are “sick” of the trope: It’s the emptiness we resent, not the strength. As Lisa“s post stresses, rejecting every capable woman reeks of insecurity—dismissing Ripley or Sarah Connor as “woke” overlooks their lasting inspiration. Sarai joins this legacy: She’s a role model for young readers, showing resilience without sacrificing femininity or feeling. In a field still skewed toward male protagonists, her tale champions shared liberation, rising above reductive tags.

In the end, Sarai shows that “strong” doesn’t have to be trope-bound. She’s a testament to the effort I put into well-rounded characters: Bending under pressure, shattering at times, but rebuilding with others’ help. In a landscape fatigued by token “girl power,” Sarai offers a revitalizing alternative—evidence that thoughtfully strong women aren’t rubbish; they’re enduring.

I’m currently seeking representation for Immortal and Godsbane, the completed foundational duology establishing the Dark Dominion sequence.

Discover more from Beyond the Margins

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.