It happens all the time. Some writer corners me at a convention or slides into my DMs with the question that’s plagued authors since someone figured out you could make money with words: “Should I write what I love or write to market?”

I tell them they’re asking the wrong question.

This isn’t either-or, despite what the “writing community” wants you to believe. The writing world has manufactured a false binary that does more harm than good—this narrative where caring about your audience somehow diminishes your artistic authenticity, or where following your passion automatically means commercial suicide. It’s complete bullshit, and it’s keeping writers from building sustainable careers doing what they actually love.

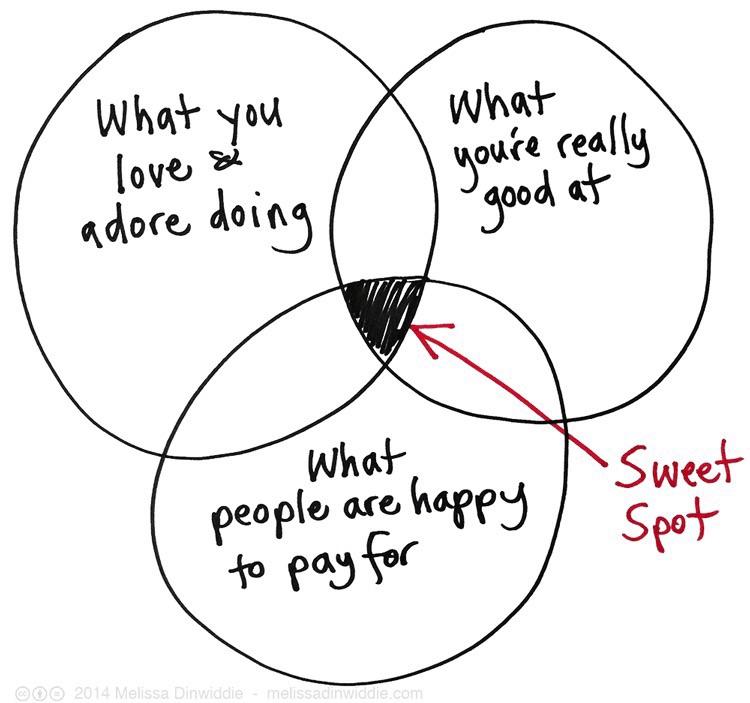

The real question isn’t whether to choose passion or profit. It’s this: “Where does what I genuinely love writing intersect with what readers are actively hungry for?”

That’s where I’m building my career—The Widow’s Son, the Doomsday Recon trilogy I created and wrote for WarGate Books, my new Dark Dominion sequence I’m shopping around. And it’s kept me sane in an industry that loves making writers feel like they have to choose between artistic integrity and paying bills.

Find Your Readers

Most of that tired “passion versus profit” debate fundamentally misses there are massive, sought-after market segments that publishers and agents actively hunt for—and you can find a home there with what you’re passionately writing about if you’re willing to thread the needle a bit to nail the sweet spot.

I’m not saying sell out.

I’m just saying be… flexible.

My particular market goes by different names—upmarket fiction, book club fiction, literary genre fiction—but it’s all describing the same thing: the sweet spot between commercial genre fiction and literary fiction.

This isn’t some theoretical category I made up to justify my choices. Literary agents list it explicitly in their submission guidelines. Publishers have entire imprints built around it. Readers buy millions of these books every year. Authors like Ursula K. Le Guin, Margaret Atwood, Raymond Chandler, and Kazuo Ishiguro have spent entire careers here, writing genre fiction with literary ambitions—or literary fiction that refuses to be boring.

Contemporary examples? Gone Girl. Station Eleven. Where the Crawdads Sing. The Secret Life of Bees. Books that gave readers page-turning plots and beautifully crafted prose, genre scaffolding and thematic depth, entertainment and substance. Books that agents fought over and readers devoured.

The industry didn’t create this category as some marketing gimmick. They created it because readers were demanding it—genre readers tired of paint-by-numbers plots, literary readers tired of meandering character studies that go nowhere. These readers aren’t some tiny niche. They’re everywhere, hungry for books that treat them like intelligent adults who want both story and substance.

Le Guin understood this decades ago. When Margaret Atwood insisted her dystopian novels weren’t science fiction, Le Guin called her out in The Guardian, while addressing the core tension she was observing.

[Atwood’s] arbitrarily restrictive definition seems designed to protect her novels from being relegated to a genre still shunned… She doesn’t want the literary bigots to shove her into the literary ghetto.

Ursula K. Le Guin

Her point wasn’t about defending science fiction’s honor. It was about exposing the false war between “literary” and “commercial” that ignores the massive overlap between them—and the damage that artificial division does to both readers and writers.

Why I’m Not Compromising

My positioning in this market isn’t about splitting the difference or watering anything down. It’s about understanding what I actually love writing and finding readers who are hungry for exactly that.

What genuinely excites me isn’t just “military fiction” or “space opera” or “historical thrillers.” What gets me fired up to write is watching smart people use real expertise to solve complex problems under extreme pressure. I want the cipher-cracking to be the action sequence. I want political maneuvering to be the thriller. I want the thinking to drive the plot, not just support it.

In The Stygian Blades, my current WIP, my characters aren’t just running from danger—they’re actively decoding real historical ciphers (checkerboard ciphers, steganography, substitution codes) while the danger unfolds. The mental work isn’t a subplot; it’s the main event. In my Dark Dominion sequence, Sarai isn’t just reacting to being hunted—she’s navigating complex political intrigue, managing identities, strategizing revolution. The negotiation and manipulation are the action.

That’s literary ambition wrapped in genre scaffolding. Complex moral questions, psychological depth, authentic expertise, real consequences—all delivered through starship battles, firefights, and conspiracy. I’m not making readers suffer through 300 pages of introspection with no plot, but I’m also not giving them explosions without substance.

One reviewer called Born in Battle, the final installment of the Doomsday Recon trilogy, “a literary work in a military fiction trench coat with a fantasy fedora.” That’s exactly right. I write for readers who want the intelligence and moral complexity of literary fiction with the adventure and scope of genre. People who are tired of choosing between books that make them think and books that keep them turning pages at 2 AM.

Turns out there’s a hungry audience for exactly that. Genre readers who want more substance. Literary readers who want actual entertainment. They’re not separate audiences—they overlap more than publishing likes to admit.

Finding the Sweet Spot

In late 2022 WarGate Books had already proven there was real market demand for military portal fantasy with Forgotten Ruin—their hugely successful series about Army Rangers teleported 10,000 years into the future to essentially a D&D world. They’d published something they were genuinely passionate about and found a massive audience.

They saw an opportunity in this growing market, and approached me to pitch something that would fit that framework. But instead of asking me to copy what was already working, they asked what I could bring that would be uniquely mine.

I’m a former Cav Scout. I’d always wondered what would happen if you dropped a modern military unit not into the future, but into a mythical past. Not just for tactical interest, but because I was fascinated by how soldiers adapt, how they maintain unit cohesion under impossible circumstances, how military training translates to threats that have nothing to do with conventional warfare. Plus I love Mesoamerican mythology.

The result? I pitched a trilogy about a platoon of Cav Scouts in 1989 Panama getting sucked into a mythical Aztec hellscape. I was capitalizing on growing market demand while creating something entirely new within it. Personal to me because of my background. Fresh for readers who’d discovered they loved this subgenre through Forgotten Ruin.

I didn’t abandon my passion for military authenticity and character-driven storytelling or moral complexity. I just made sure I was telling that story in a way that connected with readers already looking for military fantasy. That’s not compromise—that’s strategic positioning of a distinctive voice.

The same principle applies to my Dark Dominion sequence. I’m passionate about morally ambiguous characters, complex political intrigue, space opera that doesn’t shy away from difficult questions about power, bodily autonomy, identity, redemption. But I’m not writing these books in a vacuum. I’m writing them for readers who love darker, more complex science fantasy—people hungry for stories that challenge assumptions while still delivering adventure and scope.

Sarai’s journey from amnesiac assassin to revolutionary leader is a story I crafted for readers who appreciate nuanced characters, political complexity, worldbuilding that rewards attention. I get to explore themes that matter to me—identity, faith, the cost of power—within a framework that gives space opera fans what they’re looking for.

Strategic Positioning Isn’t Gaming the System

Understanding your market doesn’t mean writing cookie-cutter fiction or abandoning what makes your voice distinctive. It means being strategic about how you use that voice to reach readers who are actively looking for books like yours.

Take Dark Dominion. When it comes time to position the first book, Immortal, on Amazon, it won’t be listed as generic “Science Fiction” and then we all hope for the best. It’ll probably go under Science Fiction > Space Opera (core genre), Science Fiction > Military (action and combat elements), andLiterature & Fiction > Genre Fiction > Political (empire, revolution, intrigue).

Why those specific categories? Because that’s where readers of Ann Leckie, Arkady Martine, and Yoon Ha Lee browse. That’s where my audience is. They’re looking for literary space opera with political depth and moral complexity—exactly what I wrote. I’m not trying to trick anyone or game the system. I’m making sure readers who want exactly this kind of book can actually find it.

That’s what “writing what you love to market” means in practice. You don’t change your book to fit a category. You understand which categories serve readers who are hungry for what you’ve written.

The market isn’t Amazon algorithms or publishing executives (though those exist). The market is readers. People who love stories, people looking for their next favorite book. And those people aren’t browsing randomly—they’re in specific places, looking for specific things. Your job is to understand where your readers are and make sure you’re on the shelf they’re browsing.

And yes, you have to figure out what shelf your work sits on, that’s marketing. But you don’t have to geld your passion.

The Practical Path

So how do you actually do this?

Start by getting brutally honest about what you’re genuinely passionate about and what you actually have the knowledge and interest to write well. Not what you think you should be passionate about. Not what seems most marketable. What genuinely gets you excited to sit down and write.

For me, that meant admitting I don’t just want to write military fiction—I want to write about soldiers using tactical intelligence under pressure. I don’t just want space opera—I want political intrigue where the scheming is the plot. I don’t just want historical fiction—I want characters cracking real historical ciphers while running for their lives.

Once I got honest about what actually excited me, I could look for where that intersected with reader demand. What shelves my books sit on.

Figuring that out is where the homework comes in. Read widely in your genre. Pay attention to what readers are discussing in online communities. Look at what’s selling—but more importantly, look at what’s getting readers excited. What are they recommending to each other? What are they staying up all night to finish?

More crucially: what are they complaining is missing? What do they wish existed but can’t find? That’s where the real opportunities are. Not in copying what’s already successful, but in identifying gaps between what readers want and what’s currently available.

When I looked at military fantasy, I wasn’t trying to copy Forgotten Ruin’s success—I was trying to understand what readers loved about it so I could deliver that experience in my own way, while also filling a gap (mythical past instead of far future, Mesoamerican mythology instead of European fantasy, brutal military accuracy instead of jingoism).

When I study space opera trends, I’m looking for readers who love authors like Leckie and Martine but wish more books tackled similar themes with different approaches. That’s the gap Dark Dominion fills.

Find where your genuine interest overlaps with reader demand. That’s where you can write with authentic passion while creating something that connects with an audience actively looking for it.

The Long Game

Writing what you love to market isn’t a get-rich-quick scheme. It’s a sustainable approach to building a career where you can keep doing what you love while reaching readers and paying bills. It’s about playing the long game instead of chasing whatever’s hot this month.

I’m not saying it’s easy. I’m certainly not claiming I’ve got it figured out. Finding that balance takes time, experimentation, probably a few failures. But it’s worth pursuing because it gives you a foundation you can build on. When you’re passionate about what you’re writing and reasonably confident there’s an audience for it, you can weather the inevitable rejections, lukewarm reviews, and market shifts that are part of this business.

The writing world loves its false binaries. Literary versus commercial. Plot-driven versus character-driven. Traditional versus indie. But the most interesting work—often the most successful—happens in the spaces between these artificial divisions.

Stop asking whether you should write what you love or write to market. Start asking how you can write what you love in a way that serves readers who are hungry for exactly the kind of story only you can tell. That’s not compromise. That’s understanding your vision exists in conversation with readers, and those readers matter.

The market isn’t your enemy. Your passion isn’t a liability. Find where they meet, and that’s where you’ll build something that lasts.

Discover more from Beyond the Margins

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.