Kids playing D&D these days seriously underestimate the effectiveness of what is perhaps the most versatile and valuable item in your dungeoneering arsenal.

It’s time we had a serious discussion about the 10’ pole.

The Golden Age of Paranoia

There was a time—a glorious, brutal time—when entering a dungeon meant accepting that the floor itself wanted you dead. Back in the AD&D days, marching order wasn’t just a suggestion your DM made while you were checking your phone. It was a survival strategy. Who’s in front? Who’s got the pole? Who’s watching for ceiling traps? These weren’t rhetorical questions. They were the difference between “we found treasure” and “Steve’s character got bisected by a swinging blade trap in the third corridor.”

Every 10-foot square was a potential TPK waiting to happen. Pressure plates. Pit traps. Tripwires connected to gods-know-what. Floors that looked solid but weren’t. Ceilings that looked stable but definitely weren’t. The dungeon wasn’t just a combat arena with mood lighting—it was an active participant in your demise, and it had been planning your funeral since before you rolled your character.

AD&D taught an entire generation that dungeon floors were more dangerous than the monsters. Because at least you could see the monsters coming.

Modern 5E? Players kick down doors like they’re auditioning for an action movie. They stride boldly into obviously trapped corridors because the game has trained them to expect the DM will telegraph danger through Perception checks and balanced encounter design. The philosophy has shifted from “explore carefully or die horribly” to “be awesome and look cool doing it.”

Which is fine, if you like your characters having spines.

What Even Is a 10’ Pole? (For the Uninitiated)

For those of you who started with 5E and think a 10’ pole is some kind of weird medieval fishing rod, let me enlighten you: it’s exactly what it sounds like. A pole. Ten feet long. Usually wood, occasionally metal if you’re feeling fancy.

In AD&D, it cost 2 copper pieces and weighed 7 pounds, which meant most characters cared more about not carrying it than the party rogue cared about actually checking for traps. This created an interesting dynamic where the fighter—already lugging around 60 pounds of armor and weapons—would inevitably end up carrying the pole because “you’ve got the highest Strength score.”

The 10’ pole had one job: keep you from touching dangerous things with your actual body. It was the medieval fantasy equivalent of “poke it with a stick and see what happens,” except the stick was tall enough to check the ceiling and long enough to test the floor three squares ahead.

It was, in essence, the most important piece of equipment you’d never see illustrated on a character sheet.

Practical Applications Your DM Doesn’t Want You to Know About

Trap Detection 101

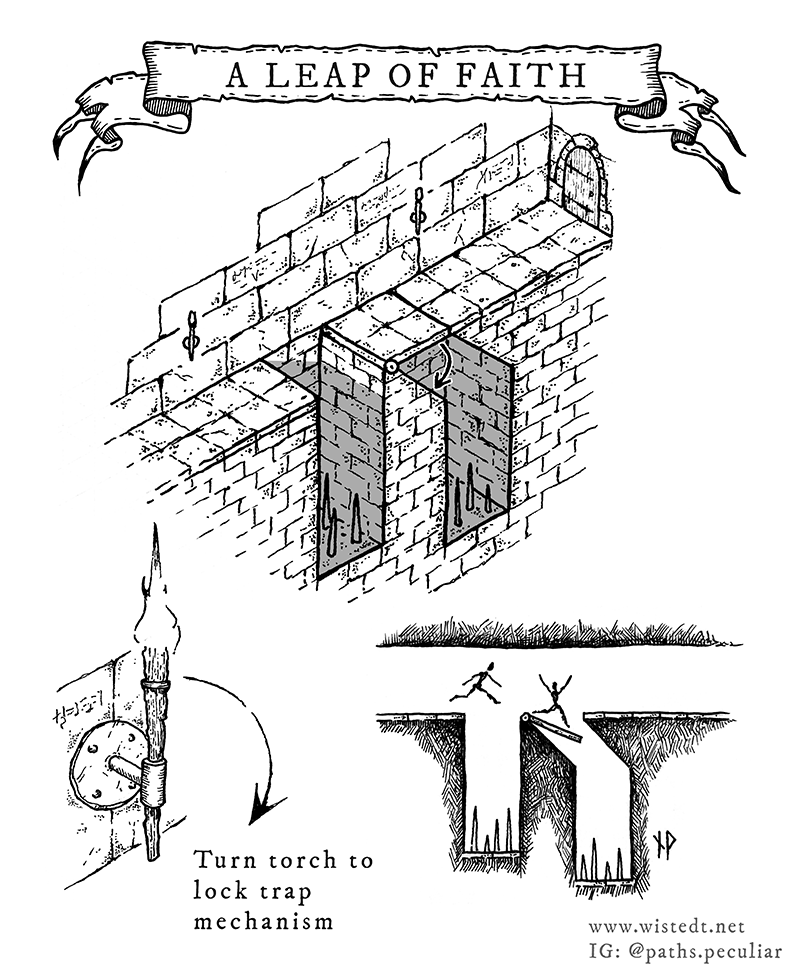

Let’s start with the obvious: poking things to see if they kill you. Pressure plates were everywhere in old-school dungeons. Everywhere. That innocent-looking flagstone three squares ahead? Probably triggers a poison dart trap. The slightly discolored tile near the door? Pit trap to a spike-filled basement. The ornate floor panel that’s clearly decorative? Congratulations, you just released a swarm of stirges.

The 10’ pole was your primary diagnostic tool. You didn’t roll Perception and hope the DM felt generous. You prodded every suspicious surface from a safe distance and learned through painful trial and error what “suspicious” meant in this particular dungeon.

In AD&D, checking for traps meant systematically testing the environment. In 5E, you roll a d20, add your proficiency bonus, and trust that the DM will tell you if something’s about to kill you. One of these approaches results in characters who survive to second level. The other results in characters with functioning spines and a healthy respect for dungeon architecture.

The Ceiling Inspector

Here’s a fun fact modern players don’t know: in old-school D&D, you were supposed to look up. Regularly. Because dungeon ceilings were bastards.

Piercers—those lovely cone-shaped monsters that looked exactly like stalactites until they dropped on your head. Ceiling-mounted blade traps. Unstable cave formations waiting for vibration to trigger a collapse. That dark patch overhead that’s definitely just shadows and absolutely not a colony of rot grubs.

The 10’ pole let you tap the ceiling ahead of you like a blind person navigating an obstacle course. Which, let’s be honest, you basically were. Most dungeon corridors weren’t well-lit. You had maybe a torch or lantern creating a 30-foot radius of “probably won’t die immediately” surrounded by infinite “definitely will die.”

Modern D&D assumes everything important happens at eye level because encounter design puts the interesting stuff where players will see it. Old-school D&D put the interesting stuff wherever would most efficiently kill you, and the ceiling was prime real estate.

Lever Actuator Extraordinaire

See that suspicious lever on the wall? Don’t touch it. Seriously. Do not touch it with your hand.

Use the pole.

I cannot stress this enough. In old-school dungeons, levers did one of three things: opened a door, released a trap, or did both simultaneously because the dungeon designer was a sadist. The 10’ pole let you operate mechanisms from a safe distance, which meant when the lever released poison gas, you were 10 feet away instead of directly in the cloud.

Compare this to the modern 5E approach, which is: “I pull the lever.” No investigation, no caution, just raw confidence that the DM won’t kill you for interacting with an obvious plot device. Sometimes this confidence is rewarded. Sometimes Steve’s new character gets to meet the party at the tavern next session because the old one got dissolved by acid.

The 10’ pole says: “I’m going to operate this suspicious mechanism, but I’m going to do it from over here, where my face is less likely to melt off.”

The Poor Man’s Bridge

Small gaps in the floor? Test them with the pole. Suspicious-looking floorboards? Pole. Stream that’s probably only two feet deep but might actually be a camouflaged 20-foot pit? You guessed it—pole.

The 10’ pole was also surprisingly useful for actual bridging. Lay it across a gap, test if it holds weight, use it as a handhold. Sure, it’s not rated for heavy loads, but it’s better than trusting that the stone ledge is actually stone and not a cunningly painted illusion over a lava pit.

Modern characters just jump gaps because they’ve got decent Athletics scores and trust that the DM won’t put an un-jumpable chasm in their path without providing a rope or magic item solution. Old-school characters tested everything because they’d seen what happened to the overconfident.

Combat Applications (Yes, Really)

The 10’ pole wasn’t just for traps. It had surprising utility in combat, especially against enemies you really didn’t want to touch.

Gelatinous cubes, for instance. Transparent, dungeon-corridor-sized, and happy to digest you slowly. The 10’ pole let you maintain a respectful distance while prodding it toward a different corridor. Same with oozes, slimes, and anything else that dealt acid damage on contact.

It was also excellent for the eternal adventuring question: “Is it really dead, or just pretending?” Nothing says “let’s be sure” like poking a suspicious corpse from 10 feet away. If it gets up, you’ve got a head start. If it doesn’t, you’ve avoided the embarrassment of getting ambushed by something you thought you’d already killed.

And let’s not forget trip attacks. A 10-foot pole across a narrow corridor at knee height? That’s an improvised obstacle that doesn’t care about your enemy’s AC. It cares about their Dexterity save.

The pole was the Swiss Army knife of “I don’t trust this situation.” Which, in a dungeon, was every situation.

Why Your 5E Character Doesn’t Carry One

Here’s the thing about modern D&D: it doesn’t want you to carry a 10’ pole. The game’s design philosophy has fundamentally shifted from “cautious exploration” to “heroic adventure,” and the 10’ pole is a relic of a more paranoid time.

In 5E, you’re assumed to be competent. You’re heroes, not zero-level schmucks hoping to survive long enough to earn a character class. The game wants you to stride boldly into danger, trust your abilities, and look cool doing it. Spending twenty minutes poking the floor doesn’t make for cinematic gameplay. It makes for a session where you traveled 30 feet down a corridor and everyone’s checking their phones.

Most 5E DMs don’t track encumbrance with any rigor. You’ve got a Bag of Holding or you just handwave carrying capacity because nobody wants to do the math. This means there’s no real cost to carrying ridiculous amounts of equipment, but also no incentive to carefully consider what you bring. The 10’ pole weighs 7 pounds, which matters in AD&D where you’re counting every pound against your Strength score. In 5E? Who cares? Carrying capacity is more of a suggestion than a rule.

Here’s the real tell: check the starting equipment lists for 5E classes. You know what’s not there? The 10’ pole. It’s not even in the standard equipment packs. You want one? You have to specifically ask for it, which means you have to know it exists, which means you probably learned about it from some grognard on Reddit talking about the good old days.

The game has been streamlined for a different style of play. Combat is tactical and engaging. Social encounters are mechanically supported. Exploration is… well, exploration is mostly “roll Perception” and hope the DM tells you something interesting. The methodical, trap-checking, ceiling-poking gameplay of old-school D&D doesn’t fit the modern design ethos.

Which is fine! 5E is a good game. It’s approachable, it’s fun, and it doesn’t require you to spend half the session arguing about marching order.

But it also means an entire generation of players doesn’t understand why anyone would need a 10-foot wooden pole.

How to Bring Back the Pole (And Why Your Players Will Hate You)

So you’re a DM who wants to run an old-school dungeon crawl. Maybe you picked up Tomb of Horrors or some other classic module and thought, “This will be fun!” Maybe you’re running an OSR system. Maybe you just want to teach your players that dungeons are supposed to be dangerous.

Here’s how to make the 10’ pole relevant again without making your players want to quit:

Telegraph the danger early. If the first corridor has an obvious pressure plate trap that the players can see from a safe distance, they’ll learn that checking for traps is important. If the first trap is hidden and instantly kills someone, they’ll learn that you’re a jerk. There’s a difference between “deadly but fair” and “gotcha.”

Reward creative tool use. When a player says, “I use my 10’ pole to check the ceiling,” don’t just say “okay, nothing happens.” Describe what they find. Give them information. Make them feel smart for thinking to check. If there is a piercer up there, let them spot it before it drops. If there isn’t, mention the unstable stalactites that would’ve fallen if they’d been noisier.

Make environment interaction matter. If the dungeon is just a series of combat arenas connected by hallways, nobody needs a pole. But if the environment itself is a challenge—if floors can collapse, if ceilings can fall, if walls might be illusions—then tools become valuable.

Don’t punish players for not having genre knowledge. If your players are used to 5E, they don’t know that they’re supposed to check every 10-foot square for traps. Teach them gradually. Start with obvious dangers and escalate to subtle ones. Don’t TPK the party in the first room because they didn’t know the game you were playing.

Track resources, but don’t be a tyrant about it. Encumbrance matters if you want the 10’ pole to be a meaningful choice. But don’t spend 30 minutes calculating exact weights. Use simple rules: you can carry what’s reasonable, and a 10-foot pole takes up space. If you’re crawling through a 5-foot-high tunnel, that pole is a problem.

Balance old-school challenges with modern expectations. Your players probably expect some combat, some roleplaying, and some problem-solving. A dungeon that’s nothing but trap-checking gets tedious. Mix it up. Let the pole be useful, but don’t make it mandatory for every single room.

The goal isn’t to recreate AD&D perfectly. The goal is to capture that sense of danger and creative problem-solving that made old-school dungeons memorable, while still running a game that’s actually fun for modern players.

Some of your players will love it. Some will tolerate it. Some will ask why you’re making them roll to check for traps when they’ve got a +9 Perception and shouldn’t the DM just tell them where the traps are?

Those last players need to learn what the 10’ pole can teach them.

Respect the Pole

The humble 10’ pole represents a whole philosophy of play. It’s about careful exploration over cinematic action. Player skill over character stats. Creative problem-solving over “I roll Perception.”

It’s about understanding that in a proper dungeon, the environment is as dangerous as the monsters. Maybe more dangerous, because at least monsters have to roll initiative.

Modern D&D has moved away from this style of play, and that’s okay. The game is more accessible now, more streamlined, more focused on telling heroic stories than on simulating deadly dungeon delving. But something was lost in that transition. A certain tension. A certain paranoia. The understanding that your character’s survival depends on your decisions, not just your die rolls.

The 10’ pole is a relic of that older game. A time when dungeons were supposed to be survived, not just conquered. When “we made it out alive” was a victory worth celebrating.

Next time you’re gearing up for a dungeon crawl, spend those 2 copper pieces. Strap a 10-foot wooden pole to your pack and ignore your party’s jokes about overcompensating. When that pressure plate triggers a pit trap and you’re standing safely 10 feet back with your pole fully extended, watching your less-prepared companions plummet into darkness, you’ll understand.

The 10’ pole isn’t just equipment. It’s a philosophy.

Also, it keeps you from falling into pits.

Which, let’s be honest, is reason enough.

Discover more from Beyond the Margins

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.