This isn’t just literary analysis. It’s a love letter to the writer who showed me the way. To the man who made me want to be an author. To the trilogy that proved this kind of fiction could exist even if it didn’t find commercial success. To the tradition of uncompromising honesty in fiction.

I own physical copies of everything Lloyd Alexander ever published, many as signed first printings. I’m also a veteran who writes science fiction and fantasy exploring questions about justified violence, political revolution, and the moral costs of war. I’ve spent years wrestling with characters who must decide when—if ever—violence serves a noble cause, who carry the weight of decisions that save some lives by taking others, who discover that overthrowing tyrants is easier than building just governance.

Lloyd Alexander laid the foundation.

I’m just trying to build on it.

His Westmark trilogy stands as his most sophisticated and morally complex achievement, yet it remains dramatically overshadowed by his beloved Chronicles of Prydain despite winning the 1982 National Book Award. Prydain has sold more than two million copies with approximately 240,000 Goodreads ratings combined.

The three Westmark novels? Just 10,900 total ratings.

A 22-to-1 disparity.

The disparity is worth far more than bland academic analysis. Westmark represents a literary tradition that desperately needs continuation. It’s adventure fiction that treats serious philosophical questions with uncompromising honesty. It’s political fiction for young readers that respects their intelligence. It’s war literature drawn from combat experience that refuses to simplify moral complexity.

And it does something increasingly rare in young adult publishing—it offers male protagonists whose depth comes from intellectual and moral development rather than competence porn and romantic relationships.

I write in Alexander’s tradition. I can’t help it. His writing formed my foundation, and my characters often wrestle with his central question: can you sacrifice innocents for a greater cause? When do the ends justify the means?

My protagonists face the exact dilemma Alexander explored—idealistic revolution confronting brutal reality. When my character Lušana in Godsbane tells Sarai “To win this war, we all must become devils,” and Sarai rejects means-and-ends justifications, insisting “I won’t become who I’m trying to defeat,” she’s having the conversation Alexander staged forty years earlier between Theo and Florian about omelets and eggs.

In Born in Battle, my character Captain Brown tells a young warrior struggling with changing traditions: “Blindly following laws and traditions leads to rigidity and the death of a people. To survive the winds of change you must be flexible, like a reed. Hold true to the spirit of your traditions, but avoid clinging too tightly to the letter of the law.”

That’s Alexander’s thinking—moral clarity about principles while honoring complexity about application.

The Westmark trilogy deserves rediscovery not just as historical artifact but as living text. Let me show you why it failed commercially, why it matters critically, and why contemporary writers—myself included—keep returning to the questions Alexander refused to answer.

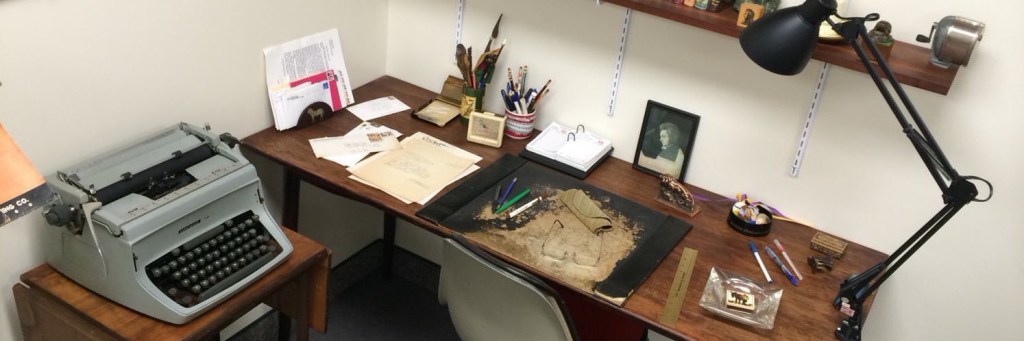

Alexander’s Personal Reckoning: Keeping the Demons

Alexander wrote these books during what he described as a “profoundly disturbing and painful emotional experience.” That phrase comes from a 1989 interview with Michael O. Tunnell, where Alexander admitted the content and themes were “very meaningful and very painful” to write about.

The source of that pain?

World War II combat service.

[V]ague shadows of Westmark and the volumes that followed had been in my head for half a dozen years before I was able to put a word on the page… not only the conflict between good and evil but—far more difficult—the conflict between good and good.

Lloyd Alexander

I understand something about writing war fiction that draws on experience you can’t fully articulate—not my own perhaps (I’m not a combat veteran), but those of whom I’ve served with, am friends with, and the deeply personal memoirs I’ve read and internalized. I’ve made the psychological toll of combat my life’s research. My characters carry trauma they can’t name. In Born in Battle, my protagonist reflects: “War is so ugly… There will always be evil men—and women—given to violence. And so we must take up arms and respond with violence in turn. It is ugly. But it is the price we warriors must pay to defend the defenseless.”

That’s the tension Alexander lived with.

That’s the tension he refused to resolve.

In his 1986 essay “Future Conditional,” Alexander explained that “vague shadows of Westmark and the volumes that followed had been in my head for half a dozen years before I was able to put a word on the page.” The questions haunting him: the uses and abuses of power, “not only the conflict between good and evil but—far more difficult—the conflict between good and good,” and whether violence can ever be justified even in noble causes.

Good versus good.

Not the easy battle between righteousness and evil, but the agonizing choice between competing goods. Between saving lives by taking them. Between preserving peace through violence. Between idealism and survival.

Then this passage, which I’ve returned to again and again: “More surprisingly, I found myself dredging up distant memories of what I had seen and known myself in combat. I did not find answers to questions raised and I expect I never will.”

He wasn’t seeking catharsis. “This wasn’t an attempt to exorcise my demons,” he wrote. “No, I keep and cherish those demons. I like to believe they’re my conscience.”

I keep and cherish those demons.

That line unlocked something for me.

I don’t write about war’s moral complexity despite finding it disturbing—I write about it because I find it disturbing. In Godsbane, when my character Mikhael tells Sarai about witnessing children dying on scaffolds and entire villages reduced to dust by nanoplagues, he’s not trying to shock her into accepting violence. He’s showing her what haunts him. What should haunt anyone who understands war’s stakes.

Alexander understood that the questions matter more than the answers.

The discomfort matters.

The refusal to provide easy resolution matters.

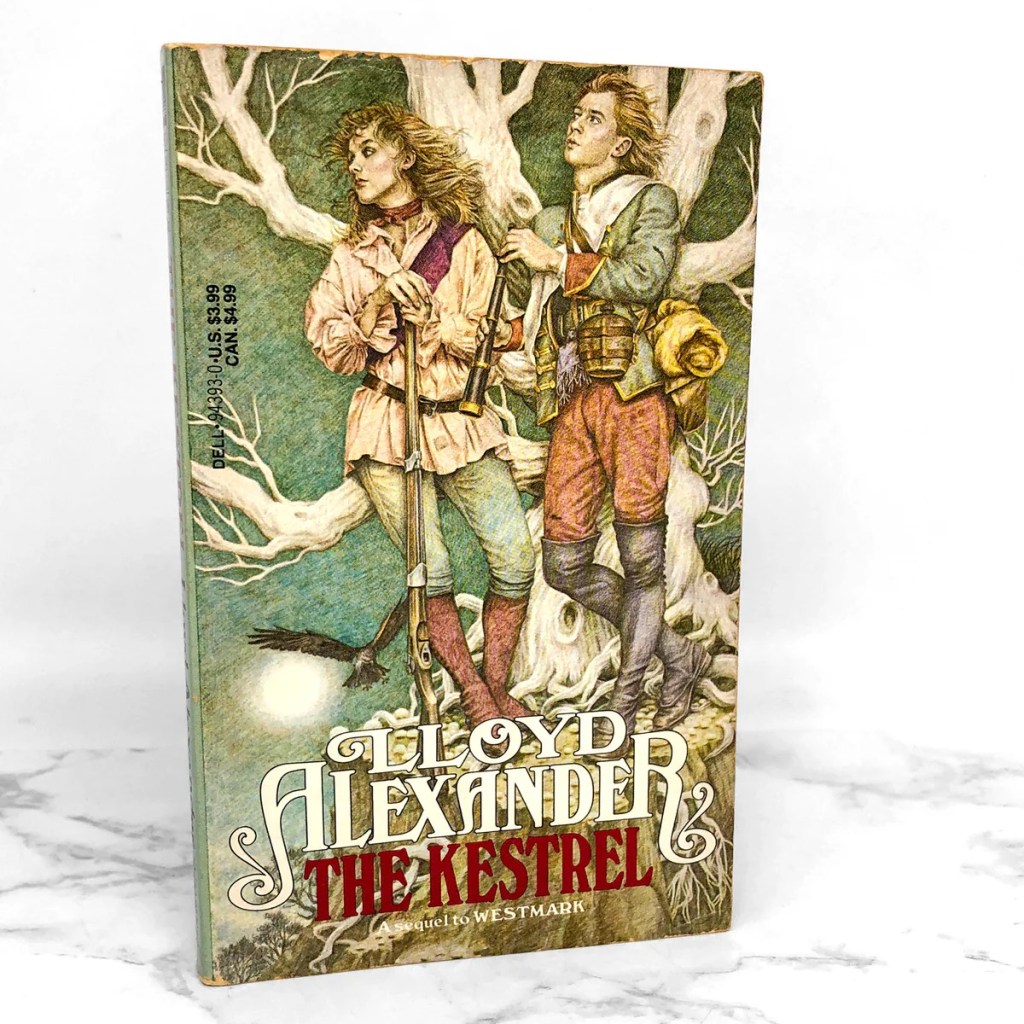

The resulting trilogy—Westmark (1981), The Kestrel(1982), and The Beggar Queen (1984)—draws from specific historical sources. Alexander cited pre-Revolutionary France, figures like Alessandro Cagliostro and Napoleon, and crucially, Francisco Goya’s paintings of war’s brutality. The capital city Marianstat came directly from postwar Paris, where he’d been stationed.

The dedication of Westmark encapsulates the moral ambiguity driving the work: “For those who regret their many imperfections, but know it would be worse having none at all.”

Perfect people make perfect monsters.

The awareness of your own capacity for wrong—that’s conscience. That’s what keeps you human when violence becomes necessary.

In his 1982 American Book Award acceptance speech, Alexander articulated his philosophy for writing honestly to young people: “We must not be intimidated or, worse, intimidate ourselves into telling less than we know. Above all, we cannot be afraid to tell what we do not know or have been unable to learn. We owe it to our young people.”

We owe it to our young people.

That obligation drives my work. When I write characters wrestling with impossible choices—when Sarai in Godsbane refuses to accept that she must “become devils” to win, when Brown in Born in Battle acknowledges “I’ll forgive Dietrich for what he did to your people after he’s dead”—I’m honoring Alexander’s commitment.

Tell them the truth. Trust their intelligence. Don’t provide false comfort.

More surprisingly, I found myself dredging up distant memories of what I had seen and known myself in combat. I did not find answers to questions raised and I expect I never will.

Lloyd Alexander

Fantasy scholars James S. Jacobs and Michael O. Tunnell, in their 1991 bio-bibliography, noted the trilogy “became Alexander’s opportunity to treat some favorite themes with uncompromising honesty: the brutality and senselessness of war, how oppression bruises the gentle spirit, and how even the mildest individual must sometimes fight against an oppressor.”

That commitment to unflinching honesty defines Westmark.

It also limited its commercial success.

Critics Loved It. Didn’t Matter.

Westmark received strong reviews in 1981. Jean Fritz wrote in The New York Times Book Review that “Lloyd Alexander does not answer questions; he raises them,” praising the book’s refusal to provide easy solutions. School Library Journal called it a Best Book of the Year, citing “rich language, excellent characterization, detailed descriptions and a dovetailed plot equal superb craftsmanship.” The Horn Book Magazine’s Ethel L. Heins noted it “engagingly portrayed ‘the age-old perplexities of right and wrong, human weakness and decency, the temptation of power, and the often unclear call of conscience.’”

The 1982 National Book Award for Children’s Fiction represented the trilogy’s critical peak.

Then the trajectory shifted.

Reviews for The Kestrel and The Beggar Queen turned mixed. Critics acknowledged ambition while noting uneven execution. By the final volume, the consensus seemed to be: this is ambitious, sophisticated, thought-provoking work that might tire “casual young adult readers.”

(Translation: too complex for kids, too simple for adults. The kiss of death in publishing.)

Before anyone dismisses these criticisms: the reviewers weren’t wrong. The trilogy is uneven. The Kestrel shifts violently from adventure to psychological warfare. The Beggar Queen refuses narrative payoff. The pacing lurches between breakneck action and philosophical debate.

This wasn’t an attempt to exorcise my demons… No, I keep and cherish those demons. I like to believe they’re my conscience.

Lloyd Alexander

But here’s what those critics missed: that unevenness reflects war’s reality. Combat doesn’t maintain consistent tone. Revolution doesn’t resolve cleanly. The “flaws” are features—Alexander refusing to smooth rough edges because life doesn’t smooth them either.

The trilogy makes readers uncomfortable.

Good.

Comfort was never the point.

Later critical reassessment has been consistently enthusiastic. The “Quid Plura” blog series on Alexander (2008-2012) declared: “The Westmark series—Westmark, The Kestrel, and The Beggar Queen—is Alexander’s masterpiece, a moving and mature story about the morality of violence and the profound cost of revolution and war. It deserves to be better known.”

A 2015 blog post concluded: “By the end, however, the Westmark Trilogy is nothing less than Lloyd Alexander’s long meditation on the Age of the Enlightenment in Europe, one that’s remarkably mature and nuanced. These are books about the impact of the printing press and widespread literacy, on the rise of humanistic ideals, on absolutism and the end of monarchy, on the changing nature of warfare and, above all about revolutions.”

But scholarly attention remained limited. Prydain received Michael O. Tunnell’s comprehensive reference work The Prydain Companion and extensive academic analysis. Westmark generated far fewer scholarly articles.

The 2012 School Library Journal ranking of all-time best children’s novels included The Book of Three at #18 and The High King at #68.

No Westmark titles appeared.

The Goodreads Gap

Prydain’s five books: approximately 240,000 ratings combined.

Westmark’s three: 10,900 total.

Breaking it down: The Book of Three alone has 82,629 Goodreads ratings with a 3.98 average. Westmark has 4,847 ratings (3.93 average). The Kestrel drops to 3,130 ratings. The Beggar Queen to just 2,926—reader attrition across the trilogy.

Publishing history reinforces the gap. Prydain has been continuously in print for 60 years, with multiple cover redesigns, boxed sets, audiobooks, translations into more than 20 languages.

Westmark? Fewer reprints. Fewer editions. No boxed sets. Multiple readers mention difficulty finding copies, particularly of The Kestrel.

The trilogy isn’t even available in eBook.

The Disney factor cannot be overstated. The Black Cauldron (1985) flopped commercially, earning just $21 million against a $44 million budget. But it provided cultural amplification Westmark never received. The film kept Prydain visible through decades of home video releases.

Westmark received no adaptation of any kind.

Why It Failed (And Why That Matters)

I understand why Westmark failed commercially.

I’m writing books that face similar challenges.

Prydain fits squarely into high fantasy—wizards, magic swords, oracular pigs, enchanted cauldrons. Readers and librarians immediately understood what it was and where it belonged.

Westmark confounds easy categorization. Though often shelved as fantasy, it contains virtually no fantastical elements. No magic. No mythological creatures. Nothing that violates natural laws. The Encyclopedia of Fantasy classified it as “Graustarkian adventures.” Others call it historical fiction set in a fictional 18th-century European kingdom.

My own work faces this. Born in Battle features magic and dinosaurs and parallel dimensions, but it’s fundamentally literary fiction exploring questions about cultural survival, justified warfare, and the cost of defending your people.

Where does that shelve? Science fiction? Military fantasy? Adventure? Literature?

The ambiguity creates marketing paralysis.

In his 1965 essay “The Flat-Heeled Muse,” Alexander articulated his fantasy philosophy: “Fantasy presents the world as it should be… Sometimes heartbreaking, but never hopeless, the fantasy world as it ‘should be’ is one in which good is ultimately stronger than evil, where courage, justice, love, and mercy actually function.”

Prydain delivers that promise. Taran becomes High King. Arawn is defeated.

Westmark offers no such comfort.

Characters realize “people are not essentially good. War proves that.” The trilogy ends not with triumph but with Queen Mickle abolishing the monarchy and going into exile—a deliberately anticlimactic ending emphasizing the hard compromises of governance over fantasy heroism.

Multiple reviewers describe the trilogy as having “more tragic deaths than Game of Thrones” with violence portrayed in visceral detail: a dead friend resembling “a ‘side of beef’ more than a man, with a mouth full of clotted blood like ‘red mud.’”

That’s the reality I write.

That’s not gratuitous—that’s the cost.

When my character in Born in Battle reflects on passing destroyed villages where there’ll be no survivors, where children have been taken captive, and acknowledges “He prayed God would forgive him” for prioritizing the mission over rescue—that’s Westmark’s moral territory.

Much of my own work takes Alexander’s themes into even darker territory. Too dark for YA. But he taught me you can write this for young adults too. You can trust them with hard truths.

That’s why I wrote my first foray into YA fiction, Doors to the Stars.

Prydain was perfectly pitched at middle-grade readers (ages 8-12). Parents, teachers, and librarians immediately grasped the target audience. The series became a classroom favorite.

Westmark straddled uncomfortable territory. One reviewer noted it “reads both middle grade and adult at the same time.” The simple prose and fast pacing suggested younger readers, but the political philosophy, graphic war violence, and moral complexity demanded maturity.

One reader admitted: “I did not appreciate these books enough when I was nine and ten. In some ways, I just didn’t understand what was happening in them. I definitely didn’t absorb, at age nine, that Theo had killed a guy.”

Fantasy presents the world as it should be… Sometimes heartbreaking, but never hopeless, the fantasy world as it ‘should be’ is one in which good is ultimately stronger than evil, where courage, justice, love, and mercy actually function.

Lloyd Alexander

I worry about this even with my adult fiction. Is it too fast-paced for literary fiction, but too philosophical for military SF?

Readers say I’ve hit the sweet spot.

Good. That means I’m working in Westmark’s tradition—respecting reader intelligence while refusing to simplify.

Prydain arrived during the post-Tolkien fantasy boom (1964-1968) with less competition. Westmark appeared later (1981-1984) in a crowded market, after Alexander had established his reputation primarily as a fantasist. The trilogy represented a departure when audiences expected more fantasy.

The Newbery Medal carries more weight than the National Book Award for library and school adoption. Disney’s involvement, however unsuccessful, provided cultural penetration Westmark could never achieve through books alone.

Prydain delivered accessibility immediately. The stakes are clear: evil Arawn threatens Prydain, young Taran must grow into heroism. Characters like sharp-tongued Eilonwy and lovable coward Gurgi created immediate emotional connections.

Westmark demands more.

The political dynamics—monarchy versus republicanism, revolutionary cells, coup d’état, questions of justified violence—require engagement with ideas. The moral ambiguity never resolves.

Multiple readers cite the famous “omelet” exchange as haunting them for years: when revolutionary Florian says you can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs, protagonist Theo responds, “Yes. But men aren’t eggs.”

Alexander never provides an answer to Theo’s assertion.

That exchange echoes through my work. In Godsbane, when my character defends means-and-ends reasoning—“Say you could save millions of lives if you took out a target, but you knew, without a doubt, you’d kill thousands of innocents in the process. Could you make that call?”—I’m staging Alexander’s debate. When another character insists “Means and ends are a dark path, and once you go down it, you become lost in the very evils you’ve rationalized,” she’s answering Florian.

But I don’t resolve it either.

I can’t.

Alexander showed me you don’t have to.

What I’m Trying to Do

What limited Westmark’s commercial success defines why I return to it.

Uncompromising engagement with political philosophy. Realistic war trauma. Moral questions without easy answers.

Alexander’s World War II combat experience permeates every page. He explicitly acknowledged that “an awful lot of situations in Westmark” were inspired by his military service. The result is war fiction that compares favorably to adult classics like All Quiet on the Western Front and The Red Badge of Courage.

Multiple reviewers cite The Kestrel as one of the most realistic depictions of war’s psychological impact in young adult literature. The violence is never gratuitous but deeply affecting. Protagonist Theo realizes he’s “had dried blood under his nails for days” as he becomes the guerrilla leader Kestrel. Characters witness friends die in graphic detail and gradually become “hardened to the war,” showing how “war turns simple, honest men into cold-blooded killers.”

I read The Kestrel as a teenager. I believe it subconsciously influences my own writing more than perhaps anything else I’ve ever read. The way Alexander refused to flinch from war’s psychological cost—the way he showed Theo becoming someone he barely recognized, haunted by what necessity demanded—that shaped how I understood what war fiction could do. Should do. I didn’t realize it at the time I was writing Born in Battle, but on reflection that novel has The Kestrel’s DNA baked into every page.

That’s the standard Alexander set.

That’s what I’m trying to achieve, even if much of the time I’m not conscious of it.

When Alexander wrote about a character examining a dead friend resembling “a ‘side of beef’ more than a man, with a mouth full of clotted blood like ‘red mud,’” he set a standard I aim for. My characters in Born in Battle pass destroyed villages decorated with mutilated corpses while acknowledging they must still press forward and not give into despair. My warbot-turned-pacifist in Doors to the Stars teaches his young protégé that “guilt is only useful so long as it leads to atonement”—Alexander’s tradition of keeping and cherishing demons.

Westmark’s greatest literary strength lies in its refusal to provide moral certainty.

The central question—when, if ever, is political violence justified?—receives no definitive answer.

Theo constantly struggles with whether his hesitation to kill represents “a moment of conscience or of cowardice.” Revolutionary leader Florian wants to be “one of the common people but clings to his aristocratic lineage because of the adoration it engenders.” Even villain Cabbarus is described as “multi-dimensional” rather than simply evil.

The Beggar Queen contrasts three political ideologies without declaring a winner: Queen Augusta/Mickle who secretly wants a republic, moderate reformer Torrens who becomes oppressive despite good intentions, and revolutionary Justin willing to sacrifice unlimited lives for the cause.

Alexander demonstrates how each ideology contains potential for both liberation and tyranny.

That’s exactly what I’m attempting in my Dark Dominion sequence. (Yes, I’m citing my own work extensively. That’s deliberate. I’m not attempting detached literary analysis here—but I’m not trying to be self-serving either; I’m showing how the tradition lives on in my own authorship. I can’t argue Westmark represents a living tradition without demonstrating that tradition lives in my own work. Because for me this isn’t abstract. It’s deeply personal.)

My character Oqal argues for peaceful reform through compromise with power: “A violent revolution is not the answer to our people’s plight. It is not the path to our emancipation and enfranchisement. It’s a path to ruin and suffering.”

He shows my protagonist horrific visions of what war between castes would entail—entire cities wiped out by kinetic strikes, children burning, starvation and plague decimating billions. The cycle of violence with no end, the galaxy spiraling into a dark age of suffering.

Then he offers the alternative: join the dictator, become his Celestial Mother, speak mercy into his ear, free your people through patient reform rather than violent revolution.

My protagonist rejects this.

But I don’t tell readers she’s right. I show the cost of her choice. I show the cost of his alternative.

Alexander taught me that—show the competing goods, the genuine dilemmas, and trust readers to wrestle with complexity.

The Westmark trilogy’s ending—with monarchy abolished but significant characters dead and the queen in exile—emphasizes compromise and loss over triumph.

The political content draws from Alexander’s study of revolutionary history. Themes include censorship and press freedom (Theo is a printer’s apprentice forced to flee after police murder his master for violating censorship laws), student revolutionary movements, regime change, urban guerrilla resistance, and the transition from monarchy to democracy.

In book after book for children, Lloyd Alexander manages to plumb serious moral and ethical issues without mentioning religion or sex. I’m not sure many young-adult writers would have either the self-restraint or the philosophical forbearance to pull that off.

Quid Plura? blog review

This creates an unusual young adult narrative where coming-of-age occurs through political awakening and moral testing rather than romance. While Theo and street performer Mickle develop a relationship, it’s described as “a sweet and understated romance” akin to “the relationship between Katniss and Peeta at the end of Mockingjay—a love between two people who know each other’s sorrows and darkness enough to carve out their own happiness.”

The romance grounds characters but doesn’t drive the plot.

Theo’s journey centers on loyalty torn between the monarchy and revolutionaries, his evolution from innocent apprentice to hardened fighter, and his struggle with the moral implications of his actions.

That’s the model I try to follow.

My characters develop relationships, but their growth comes through moral and political testing. Through questions about power, violence, tradition, and the cost of defending what matters.

This approach addresses documented gaps in contemporary young adult publishing. Multiple sources document “the boy problem in YA”—avid male readers who “ate up middle grade but go to adult fiction and non-fiction instead of passing through YA.” Market analysis shows that “boys don’t read YA” not because boys don’t read, but because current YA is “so obviously marketed towards girls.”

A 2024 Kirkus review titled “We Need More YA Books About Gender—for Boys” noted that books “that unpack toxic masculinity in accessible and engaging ways that speak directly to boy readers—are still vanishingly rare.” National Literacy Trust reports show “the number of children and young people who say they enjoy reading is declining, and that this decline is particularly steep amongst boys aged 11 to 16.”

I’m the father of sons who fit this profile. They devoured middle-grade fantasy—Prydain included—then struggled to find YA that spoke to them. Not because they don’t read. Because they wanted substantive narratives that respected their intelligence, that explore moral complexity, that feature protagonists whose depth comes from intellectual and ethical development rather than romantic relationships and self-insert wish fulfillment. They turned to Japanese manga because American publishers aren’t serving them.

Westmark represents what’s missing, and what I’m trying to provide in my YA novel Doors to the Stars: Protagonists whose depth comes from moral development. Fast-paced adventure combined with philosophical questions. Coming-of-age through conscience and political engagement. War and violence portrayed with psychological realism. Treatment of serious themes without condescension.

One reviewer noted Alexander achieves something remarkable: “In book after book for children, Lloyd Alexander manages to plumb serious moral and ethical issues without mentioning religion or sex. I’m not sure many young-adult writers would have either the self-restraint or the philosophical forbearance to pull that off.”

That’s the craft discipline Alexander modeled.

You can explore profound questions about morality, power, violence, and governance without relying on romance or explicit content. You can trust young readers to engage with ideas.

Why It Still Matters

Modern reader engagement with Westmark, though smaller in scale than Prydain’s following, reveals the trilogy’s continued relevance.

A 2016 blog post titled “People Aren’t Eggs and the Future’s Not an Omelet” explicitly connected the trilogy to contemporary political turmoil: “As politics get ugly and dumpsters explode and people are shot in the street without evidence of criminal activity, it can be easy to despair of the world.”

The blogger described reading Westmark “not long after 9/11” when “war seemed like a no-brainer. Kill the bad guys and you will save the good guys.”

I read Westmark at a different time. But it shaped how I think about every conflict since. When my country went to war. When I watched political violence escalate. When I heard means-and-ends justifications for actions that cost innocent lives.

Alexander’s questions haunted me.

Men aren’t eggs.

The blogger continued: “The scene where Theo, after becoming a rebel leader and avenging his friends, is looking at his hands and realizing he’s had dried blood under his nails for days was chilling to me.”

That image stayed with me too.

It’s why I write about characters who carry the weight of their choices, who realize you can’t wash blood away just because your cause was just.

Goodreads reviews from 2020-2021 show readers discovering the trilogy and recognizing its distinctiveness. Multiple readers compare it to The Hunger Games for its treatment of war trauma and PTSD. Another reader noted: “There’s a lot of overlap between devotees of this series and fans of the gallant, doomed student revolutionaries of Les Mis.”

The trilogy’s relevance for readers interested in revolution, social justice, and systemic change remains potent. Alexander explores questions about justified violence, the costs of revolution, corruption of power, effectiveness of gradual reform versus radical change, and what happens after revolution succeeds.

The ending emphasizes that successful revolution requires not just overthrowing tyrants but establishing functional democratic governance—far more difficult and less emotionally satisfying than fantasy heroism.

That’s the lesson I’m exploring. In Godsbane, my character who argues for patient reform warns that deposing the dictator would create “a galactic civil war on a scale never seen before, far worse than the War of the Princes.” She asks: “Is it better to die fighting for freedom than live in chains? And what freedom is there for an emancipated people in a shattered empire? The freedom to watch their children starve? The freedom to live under the boots of oppressive warlords?”

Those are Alexander’s questions.

Revolution’s cost. Governance’s difficulty. The gap between idealistic uprising and functional society.

A 2016 reflection on modern politics referenced Westmark’s central lesson: “Both groups speak with a touch of naïveté at times, a belief that if we work out a few kinks, humanity will just be all right. Mob justice is the hope of one side. Stronger laws is the solution of the other. In between, there are a thousand different compromises.”

Westmark teaches that “nothing will fix everything, but nothing will destroy everything. We all have some measure of control over our relationships and communities.”

Alexander refuses to either glorify or condemn revolution simplistically. Characters across the political spectrum receive sympathetic treatment while their flaws are exposed. The trilogy serves, as one reviewer suggested, as “a useful stepping stone for young readers who have yet to encounter ‘All Quiet on the Western Front’ or Machiavelli’s ‘Prince’ in the high school curriculum.”

That’s the tradition I’m trying to honor in all my work, whether targeted to adults or teens.

Serious political fiction that doesn’t simplify. War literature that shows the cost. Adventure that respects reader intelligence.

The Tradition Lives

The Westmark trilogy’s relative obscurity compared to Chronicles of Prydain represents a loss I’m trying to address through my own work.

The commercial factors that limited Westmark’s success—genre ambiguity, tonal darkness, complex themes, lack of media adaptation—also define why it matters. For contemporary readers, particularly boys and young men seeking substantive adventure fiction, these three books provide intellectual and emotional challenges rare in literature marketed to adolescents.

The questions Alexander raises about power, violence, and governance remain urgently relevant.

I write military-themed fiction without jingoism because Alexander showed me it was possible. Possible to explore war’s moral complexity without simplifying. Possible to trust young readers with hard questions. Possible to write protagonists whose depth comes from ethical development rather than explicit romantic relationships or wish-fulfillment competence porn. Possible to refuse easy answers while maintaining moral clarity.

I did not find answers to questions raised and I expect I never will.

Lloyd Alexander

My character in Born in Battle echoes that thinking about principles versus rigidity. My characters in Godsbane debate whether becoming devils is necessary to win—and I refuse to provide clear resolution, following Alexander’s example of keeping and cherishing demons because they’re your conscience.

The Westmark trilogy’s critical recognition—National Book Award, sustained scholarly appreciation—confirms its literary merit even as popular success eluded it. Later critics calling it “Alexander’s masterpiece” and insisting “it deserves to be better known” aren’t wrong.

But here’s what matters more than recognition: the tradition continues.

Writers exploring war’s moral complexity. Political fiction for young adults that doesn’t condescend. Adventure narratives that trust reader intelligence. Male protagonists whose growth comes through conscience and ethical testing. Questions without easy answers about power, violence, and governance.

Alexander’s willingness to tell uncomfortable truths, drawn from his own combat trauma, created books that honor young readers’ capacity for complex thought. As he stated in accepting the National Book Award: “We must not be intimidated or, worse, intimidate ourselves into telling less than we know… We owe it to our young people.”

We owe it to our young people.

That obligation drives my work. Every time I write a character wrestling with impossible choices, every time I refuse to provide false comfort, every time I trust readers to engage with complexity—I’m honoring Alexander’s example.

The Westmark trilogy awaits readers ready to engage with fiction that respects their intelligence and challenges their assumptions about morality, power, and the costs of political change.

But more than that, it stands as proof that this kind of fiction can exist. That young adult literature can handle profound questions. That adventure and philosophy can coexist. That you can write war honestly without either glorifying or condemning it simplistically.

Alexander kept and cherished his demons. He wrote from them without seeking to exorcise them. He raised questions he never answered because the questions matter more than false certainty.

I’m trying to do the same.

Alexander wrote: “I did not find answers to questions raised and I expect I never will.”

Neither do I.

But I keep writing toward them, carrying demons I cherish, asking questions that matter, trusting readers to think alongside me.

That’s what Alexander gave me.

That’s what I’m trying to pass forward.

The Westmark trilogy deserves rediscovery not as artifact but as living tradition. As proof that this work matters. As example for writers attempting similar territory. As gift to readers capable of wrestling with humanity’s most difficult questions.

Men aren’t eggs.

Some truths don’t resolve. Some questions haunt you for decades. Some books change how you think about your craft, your obligations, and what fiction can do.

Westmark did that for me.

It can do that for others.

Alexander showed the way. The rest of us just have to be brave enough to follow.

Discover more from Beyond the Margins

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “Men Aren’t Eggs: A Love Letter to the Westmark Trilogy”