A reader sent me a DM after I posted about a scene in Junk Rat, my YA space opera reader magnet for Doors to the Stars. I’d mentioned that a 13-year-old girl kills an unconscious guard during a robbery because he saw her face—if he lives to tell, she’s as good as dead, or he’ll use it against her as leverage.

The message was thoughtful and raised a question worth exploring: “Honestly, it feels like your principle that ‘young people can handle depth and darkness’ is starting to veer into something else: writing adult literature but labeling it YA simply because the protagonist is a teenager. If age is the only distinguishing factor, then why have a separate genre at all?”

They continued: “YA, to me, is about coming of age, self-discovery, and moral evolution. So what’s the point if the teens in these stories are written as small adults—showing no meaningful difference in mindset, growth, or emotional processing?”

This isn’t pearl-clutching about darkness. It’s a sophisticated question about what actually distinguishes YA from adult fiction.

The reader has identified something real—a crisis in contemporary YA where teenagers often act like small adults, where emotional processing gets compressed into adult patterns, where the only thing “young adult” about the book is the protagonist’s age.

But my YA writing isn’t doing that.

Young adult literature has a problem, and it’s not the one people think.

The market belongs to adults now. Fifty-five to seventy percent of YA readers are adults aged 18 and over, and they’re not buying gifts—they’re reading YA as their primary fiction. Publishers responded rationally: when adults with disposable income are your primary market, why optimize for the 45% with less purchasing power? The shift to expensive hardcover releases, books requiring series commitments, marketing that prioritizes adult romance readers—it made economic sense.

But it abandoned the genre’s purpose.

Walk into any bookstore’s YA section and you’ll find seventeen-year-olds who act like college students, emotional processing that looks like adult compartmentalization rather than teenage overwhelm, relationship dynamics optimized for adult readers seeking romance instead of actual coming-of-age narratives. Publishers will market four-star “spicy” romance with detailed sex scenes to teenagers but reject books about systemic injustice, moral ambiguity, or the psychological cost of violence as “too dark.” They’ll publish books where teenagers have graphic sex but express concern about realistic depictions of teenage substance use, mental health crises, or encounters with police violence. They’ll accept chosen-one narratives where special teenagers save the world through destiny, but reject stories where flawed teenagers make difficult choices under impossible pressure.

This creates a false binary: YA equals sanitized and safe while adult fiction equals dark and real.

That’s not the distinction. The distinction is processing.

Here’s the litmus test for any book:

Does the character process trauma like a teenager or like an adult? Is there a coming-of-age arc involving self-discovery, moral evolution, identity formation? Do emotions overwhelm the character or do they compartmentalize efficiently? Are there physical manifestations of psychological stress? Does violence or trauma haunt them or do they move on pragmatically?

The answers determine the genre. Not the protagonist’s age.

In adult fiction, a protagonist kills someone, compartmentalizes the experience, moves forward with reasonable efficiency. They might have regrets, but those regrets don’t consume them. They process the event, file it away, continue their mission. This is how adults—especially trained professionals—handle trauma.

In YA fiction, a protagonist kills someone (or witnesses killing, or is complicit in killing) and the experience shakes them. They’re horrified. They carry it as moral injury. They struggle with guilt that spirals into self-destructive patterns. They have nightmares. They flinch at reminders. They question who they are and who they’re becoming. The trauma doesn’t get filed away—it lives in their body, shapes their relationships, drives their character arc.

Contemporary YA that gets this right proves the point.

In Leigh Bardugo’s Six of Crows, Kaz Brekker has severe PTSD from swimming back to shore using his brother’s dead body as a floatation device. He cannot touch anyone’s skin without triggering his trauma. The series follows him through impossible heists and deadly conflicts, and his love for Inej doesn’t magically fix him. By the end, he still has PTSD. Inej tells him directly: “I will have you without your armor, Kaz Brekker. Or I will not have you at all.” She refuses to accept him until he deals with his trauma—and that’s where the series leaves them. No easy resolution. No love-cures-all ending.

In Sarah J. Maas’s Throne of Glass series, protagonist Aelin suffers months of torture—bones broken repeatedly, forced to kneel in broken glass, flayed, healed, and tortured again in an endless cycle. When her captors attempt to burn her, Aelin fights back not from heroic determination but from fear of the PTSD she knows she’ll develop with her own fire powers if she experiences being burned. Readers describe her trauma as “realistic and maddening,” and the PTSD doesn’t resolve quickly. It lingers. It shapes her decisions. Her constant anxiety becomes a character trait.

One reader wrote: “It’s becoming more common to show characters dealing with their trauma instead of just suddenly being okay again.”

Contemporary YA that works shows teenagers processing trauma like teenagers, not like hardened adults who’ve learned to compartmentalize efficiently. Violence in YA requires showing the psychological impact. When characters walk away from violent encounters without showing signs of emotional trauma, something is wrong.

Classic YA understood this same principle.

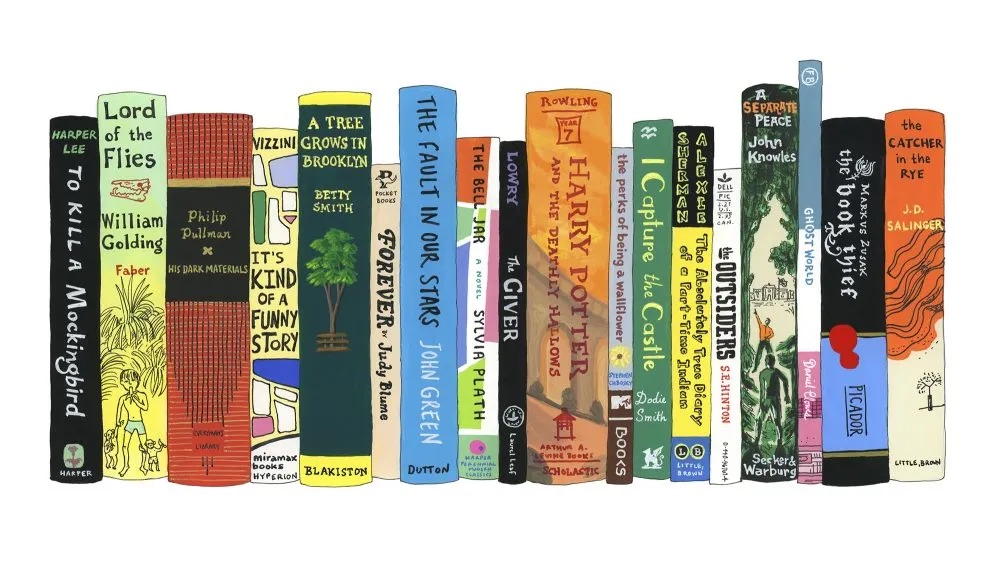

The Outsiders featured gang violence and teenage murder. Speak addressed rape trauma. Monster put a sixteen-year-old on trial for murder with profound moral ambiguity about his guilt. The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian tackled addiction, poverty, and death on reservations with profanity and humor that served the story. The Hunger Games forced children to kill each other on live television and showed PTSD, war trauma, the psychology of desensitization to violence.

These books trusted teenagers with moral ambiguity, real consequences, systemic critique, difficult questions without easy answers. They featured realistic language. They showed violence with lasting trauma, not just thrilling action sequences.

And they reflected reality.

Teenagers in extreme circumstances don’t become adults mentally just because their situations are adult. They develop survival pragmatism while still processing trauma like children—nightmares, physical manifestations of stress, emotional dysregulation, difficulty trusting. The research on child soldiers proves this. Fifty-four percent of interviewed child soldiers reported having killed someone, with an average recruitment age of twelve years old. They report feelings like “I felt happy afterwards because if you say no, they’ll kill you.” But they’re still children processing adult situations with child psychology—nightmares, hypervigilance, difficulty reintegrating into normal life. The trauma doesn’t make them adults. It traumatizes them as children who must survive anyway, developing pragmatism out of necessity while still crying, still having nightmares, still struggling with trust, still carrying their trauma in their bodies.

Let me address the scene that sparked this conversation directly.

What I posted on social media:

What actually happens is naturally more complicated and nuanced.

The 14-year-old protagonist Wulan doesn’t kill the guard. A 13-year-old girl named Cassandra does, while Wulan watches. The context matters.

Three girls—Wulan (14), Cassandra (13), and Ryn (11)—are robbing a fence named Grisk who previously cheated all of them. They’re loading stolen goods into rucksacks when a young guard enters unexpectedly. Wulan improvises, pretending to be tied up, claiming Grisk was going to sell her to the Bonemen—child traffickers. The guard believes her and is genuinely horrified.

Then Cassandra knocks him unconscious with a pipe.

She moves to kill him with her knife, telling Wulan: “He’s seen your face. He’ll talk. You’ll be a walking dead girl. Or he’ll use it against you as leverage.”

Wulan hesitates at that last word. She knows what it means. She tries to find an alternative: “We could bribe him—”

Cassandra cuts her off: “Are you not listening, girl? Only one thing you can bribe him with, and that won’t never be enough. He’ll own you forever. Might as well be sold to the Bonemen for real. You want that?”

Wulan protests: “He’s practically a kid like us.”

She reaches for Cassandra’s arm to stop her. Cassandra looks at her pointedly: “Ain’t no kids left on Miller’s World. Not you, not me, and especially not him, eh?”

Wulan nods and drops her hand.

Cassandra says: “Good, then it’s settled.”

Wulan looks away as Cassandra kills him quickly with her knife. Wulan doesn’t stop her. Doesn’t watch. Just hears the gurgle and smells the hot blood. She fidgets with Arjuna’s cord—her dead brother’s braided bracelet that she touches obsessively when stressed. She doesn’t look at the body. The first words out of her mouth are: “We need to move. Now.”

This isn’t a teenager acting like a small adult who kills coldly and moves on. This is a traumatized 14-year-old being complicit in violence she can’t prevent, processing it through dissociation and physical anxiety responses, carrying that moral injury forward. The psychological realism is baked into how she responds—not with adult compartmentalization, but with teenage horror, guilt, and an inability to fully process what just happened.

Cassandra isn’t killing because she wants to or because she’s inherently violent. She’s killing because the guard saw Wulan’s face, and in their world, that means either death or something worse. When Wulan suggests bribery, Cassandra shuts it down with brutal clarity: “Only one thing you can bribe him with, and that won’t never be enough.”

This isn’t casual violence. This is a 13-year-old who understands exactly what happens to girls in their situation when men have leverage over them. She’s protecting Wulan from a fate she clearly knows too much about.

Earlier in the story, Cassandra asks Wulan about a fresh cut on her shoulder with bad DIY stitching. Wulan answers flatly: “It was a warning.” When Ryn presses about what kind of warning, Wulan responds: “That my face would be next if I kept struggling.”

Older readers and survivors will immediately understand what happened. Younger readers will register that something bad occurred but won’t have the full horror spelled out for them.

In the novel Doors to the Stars, Wulan still carries the ugly scar on her left shoulder, and mentions all her scars have stories, and that one’s story is one she’d rather forget. That’s it. That’s all I say. The trauma informs her character—her discomfort with being touched, the walls she’s built—but I never depict it graphically or exploit it for shock value.

This is how you write about sexual violence in YA: you acknowledge it exists, you show its lasting impact on survivors, but you don’t put readers through the experience itself. Sexual assault should never be a plot point, but it’s a reality that needs to be addressed—sensitively, but addressed all the same. Survivors deserve to be recognized. Even teens.

Especially teens.

Cassandra’s line “Ain’t no kids left on Miller’s World” isn’t me writing adult fiction with a young protagonist. It’s me writing realistic survival conditions where extreme poverty strips children of childhood. She’s not a small adult—she’s a child who’s been forced to make adult calculations about survival and sexual violence. The tragedy is that Miller’s World has forced her to become someone who can kill, someone who understands the stakes well enough to know that leaving the guard alive means Wulan faces execution—or something possibly worse than death.

In the novel Doors to the Stars, Wulan is sixteen now, and carrying the weight of everyone she’s failed to save. The story follows her as she’s drawn into events far larger than herself, facing impossible choices about power, responsibility, and what she’s willing to sacrifice.

But the plot isn’t what makes it YA. Watch how she processes trauma throughout.

She cries in the shower thinking about her dead friends, frustrated that “my ghosts won’t let me enjoy even the new experience of taking a hot shower.” She fidgets obsessively with Arjuna’s braided cord—a physical manifestation of her anxiety and trauma. She has catastrophic guilt spirals: “I’m a genocidal terrorist with the innocent blood of thousands on my hands. I told her to keep breathing, and then I stole her air.”

She contemplates suicide—there’s a knife beside her bed, and she considers “it would be so easy.” When she committed violence at fourteen, she “stood there shaking and horrified at what her hands had done.” That horror defines her character for years. She physically collapses from emotional weight. She’s confused by attraction and touch because of her assault trauma. She projects toughness while being, as the narrative describes her, “deeply vulnerable underneath.”

The coming-of-age journey drives everything. She moves from isolation to tentative connection. From “everyone has an angle” cynicism to learning genuine kindness exists. From self-destruction to atonement. Her mentor—someone who also carries the weight of violence they’ve committed—teaches her: “Guilt is a signal that one has strayed from one’s path and must self-correct. But it is only a signal. To be consumed by guilt is to subvert its purpose.”

She learns she can’t save everyone alone. She finds chosen family worth the risk.

This is textbook YA: moral evolution, self-discovery, teenage emotional processing, identity formation through trauma. At every turn, Wulan responds like a traumatized sixteen-year-old, not an adult hero.

Only 32.7% of children aged 8-18 say they enjoy reading for pleasure—the lowest rate in twenty years. But these same teens still read song lyrics, news articles, fiction, comics, and fan fiction. They’re not illiterate. They’re underserved.

And they’ve found what they need elsewhere.

The manga market in the US reached $1.28 billion in 2025, with sales growing 160 percent between 2020 and 2021 alone. School librarians report manga “flying off the shelves” faster than they can restock, with students “literally climbing into return bins to get manga when they see their classmates return it.”

What does manga offer that American YA doesn’t?

Age-appropriate protagonists facing real stakes with lasting consequences. Moral complexity explored without easy answers. Authentic coming-of-age narratives where characters grow measurably over hundreds of chapters, forced to mature due to circumstances. Difficult themes American YA increasingly avoids: depression and suicide, sexual identity and assault, systemic corruption, the psychological impact of violence, existential questions about purpose and meaning.

Teens report that manga “treats teens as mature viewers” and addresses “romantic attraction, teen relationships, depression, and the despair that can come when things don’t work out” without condescension.

American teenagers are voting with their wallets. They’re saying “we want substance, not just vibes.” Traditional YA publishing isn’t listening.

When we sanitize YA, when we replace teenage psychology with adult compartmentalization, when we optimize for adult romance readers instead of actual teenagers, we lose stories that trust teenagers with complexity. We lose books that reflect what being sixteen actually feels like when the world doesn’t offer clean answers. We lose literature that shows teenagers can survive trauma, process it, and grow from it.

Classic YA trusted teenagers with weight. These books had profanity when appropriate to character. They showed violence with lasting trauma. They asked difficult questions without providing easy answers. Teenagers devoured them because teenagers don’t need protection from difficult stories. They need stories that trust them with difficulty—and then show them how to process it, survive it, and grow from it.

Let me return to that reader’s original question: Is a 13-year-old killing in a survival situation YA or adult fiction?

The answer depends entirely on how she processes it.

If she kills pragmatically, feels brief regret, then moves on efficiently—that’s adult fiction with a young body. If she kills to protect someone from sexual exploitation because she understands that threat intimately, if her friend watches in horror and dissociates, if both carry it as moral injury that shapes their character arcs—that’s YA.

YA isn’t defined by what you don’t write. It’s defined by how your protagonist processes what you do write.

Doors to the Stars launches February 24, 2026, as my attempt to reclaim what YA used to be: stories that trust teenagers with complexity, treat them like they’re smart enough to handle moral ambiguity, and reflect the weight they already carry. Not because I’m special, but because this is what the genre should be doing.

Traditional publishing said there’s no market for this. The manga boom, the literacy crisis, and readers reaching out desperately for “books that feel truly meant for them” suggest otherwise.

Teenagers don’t need protection from difficult stories. They need stories that trust them with difficulty—and then show them how to process it, survive it, and grow from it. That’s what YA is. That’s what it’s always been.

And it’s time we took it back.

Discover more from Beyond the Margins

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.